In the late 1980’s, I went to a workshop conducted by American painter Robert Colescott. Colescott had come to the museum of Beaumont, where Sheila Stewart, wife of my former colleague, Larry Leach, was Curator. It seemed like a good idea to combine some art study with a visit to friends, so off we went to Beaumont, leaving children in the care of grandmother!

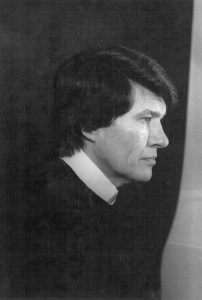

Robert Colescott (1925-2009) was as interesting a personality as he was an artist. Born in California, he was educated at U.C. Berkley as a painting student of James McCray (1912-1993). Colescott completed his undergraduate degree in 1949 and set off for Paris to hone his craft. His goal was to study with Fernand Léger, and most articles on Colescott confirm that this plan was accomplished—not without a major change in Colescott’s style, however!

Colescott arrived in Paris as a geometric abstractionist, strongly influenced by his work with McCray, and with a portfolio to present. In an interview, conducted near the time of the Beaumont workshop, Colescott elaborated on his encounter with Léger:“I presented my portfolio but he didn’t want to look at it. He felt that abstraction didn’t communicate ideas to ordinary people. And…so…the guy just wasn’t going to look at my work.”

This was a turning point for Colescott—as he said, “a 360-degree turn around.” Léger was working with the human figure, and had a group of models employed who posed for himself and his students. Colescott began to paint the figure, and from that time, was completely involved in figure painting. He worked to say something not only about the human figure but the human condition as well.

Another profound influence on Colescott was the result of a sabbatical to teach at the American University in Cairo in 1964. There, he was faced with 3,000 years of non-White culture. His figures began to change. Stylized color began to blend into bright, loose Cubist backgrounds. The time in Egypt gave Colescott new insight into the Black identity and the dilemma of race in America. Back in the U.S. and teaching at CA State College, Colescott turned to narrative figure painting, focusing on the institutional exploitation of minorities in America. He was in large company. Many California artists—especially Black artists—were infiltrating caricatures into formal work, even to the extent of painting familiar stereotypes such as Aunt Jemima. The idea of “blackfacing” Western masterpieces developed, with Colescott joining in. His paintings from the mid-1970’s include “blackface” caricatures of van Eyck’s Giovanni Arnolfini and his Bride, van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters, and even Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon. Colescott saw such work as having a dual purpose: paying homage to artists that he revered, and making a sharp cultural critique of racism. “My aim was to expose a lack of real Black faces in art and in history through exaggeration, and it was personal.”

Perhaps the best-known of his 1970’s paintings is George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware (1975.) The parody of Leutze’s 1851 masterpiece, in bright flat acrylics, was first exhibited at the John Berggruen Gallery of San Francisco. It was an affront to the art world, but yet another turning point in Colescott’s career. America was approaching its Bicentennial, and Colescott wanted to address what he saw as the great dilemma of Black patriotism. Colescott satirized and offended without regard, lampooning anything and everything in bright imagery and with a strong dose of humor.

Colescott always worked to express himself through his work. He remarked, “It is probably the only way that I can express myself openly and overtly without going to jail!” He often painted himself into a work, usually in caricature, but still easily recognizable. Stereotypes of all colors haunt his paintings, one race seeping into another.

All Roads Lead To Rome was painted in 1995. This parody of the Mona Lisa contains the inscription “Giaconda! A good Italian name…we did better then!” Colescott’s later works were more abstract and far less concerned with the human condition. One of the best known is Sleeping Beauty, a large abstract dating from 2002.

Robert Colescott taught at the University of Arizona at Tucson from 1983 until his retirement as Professor Emeritus. In 1997, he was chosen to exhibit in the prestigious Vienna Biennale, the first Black American to represent the U.S This exhibit reflected a move away from appropriation art in the pop aesthetic toward a more complex visual narrative. Colescott died in 2009 as a result of Parkinson’s Disease.

You can see a number of Colescott’s paintings in the Arthur Roger Gallery in New Orleans. Colescott maintained close ties to the city of his parents who moved from New Orleans to Oakland shortly before his birth.

I learned a lot from Robert Colescott in that workshop. His approach to the anatomy of the human figure was masterful. I learned that crowding a space was ok if the figures were placed with insight into the subject. I learned that garish colors could speak volumes if presented to enhance the subject. I learned that there could be great humor in serious and formal painting. I learned not to paint for hours in a room using gum turpentine as a thinner. The workshop had been set up in a workroom that had no ventilation and all of us, Colescott included, suffered the effects of the fumes. We finally took a lunch break to visit socially and try to rid ourselves of the throbbing heads!

Colescott worked with pure joy and abandon. He wrote a short autobiography in each painting, expressing his responses to life’s events, his fears, his concerns. While his work always startled and often offended, Colescott remains one of the most important figures in 20th-century art and certainly the single most important Black artist in America.