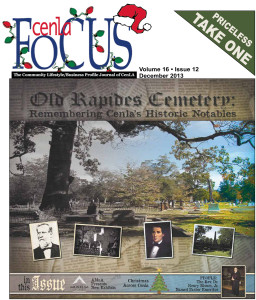

There is no better place to learn than the seven acres that define the old Rapides Cemetery on the Pineville side of the Red River. In that enclosed space lay the people whose lives still continue to shape our own. Laid out on lands that once belonged to Etienne Marafret Layssard, the first commandant of the Poste de Rapides, the Rapides Cemetery is the oldest burying ground in the civil parish. Although many of the early graves and tombstones have fallen victim to time and vandalism, some dating as far back as the early 1800’s can still be found. The oldest marked grave that can be seen today is that of Sosthene Baillio, a boy of fifteen, who died in 1809. For over 200 years, this site has absorbed the grief and loss and pain that have shaped our community.

It is easy to forget the difficulties that faced the earliest settlers of this region. Flood, famine, drought, war and pestilence plagued those who tried to carve out a foothold here in the heart of a wilderness. The graves of many of our earliest settlers remind us of those difficult and trying times. Alexander Fulton, the founder of Alexandria, fled from his home in Pennsylvania because of his involvement in the Whiskey Rebellion. To avoid trial for treason against the United States, he fled to Spanish Louisiana and became a merchant and Indian trader, amassing a fortune in land. He also found a wife, Henrietta Wells, whose grave still stands today. Fulton’s grave, like so many others, is unmarked. The earliest families are all represented here: Layssard, Baillio, Deville, Lacaze, LaCour, Poiret and many others.

Pierre Baillio, the builder of Kent Plantation House, is bur

Veterans of all wars are buried here, including several generals such as General Isaac Thomas, Jr. and General David T. Stafford, the son of General Leroy Stafford who fell at the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. General D.T. Stafford was head of the Louisiana National Guard and was responsible for the annual summer encampment of the old LSU grounds. That annual encampment grew into training camps during the First and Second World Wars. The V.A. Medical Center now sits on the old campgrounds. General Stafford and his wife, Amy, the daughter of George Mason Graham, lost several children of their own, but faithfully served as sponsors for many of the Confirmation classes at the Cathedral; in fact, the front window of the Cathedral is dedicated to his memory.

Since the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, our community has always been a southern “courthouse” town. Alexander Fulton himself served as the first postmaster and the first coroner of the “county of Rapides”. So, it is not surprising to find so many markers for judges and lawyers throughout the grounds. Judge Gervais Baillio, who served as district judge for both Avoyelles and Rapides Parishes before the Civil War, is buried in the Baillio plot. Judge Henry Boyce, for whom the town of Boyce is named, is buried here, together with Judge John Clements, who served as constable and tax collector in 1861. Judge Henry Daige is here together with Michael Ryan, one of Alexandria’s notable antebellum attorneys who helped lead the opposition to carpetbagger rule during Reconstruction.

Politicians of all kinds can be found on courthouse steps, and the Rapides Cemetery is full of them. One of the most notable and notorious is Governor James Madison Wells. A Rapides Parish planter and lawyer, Wells opposed secession and went on to serve as Lt. Governor of Louisiana under Union occupation, and was elected Governor of the State in 1865. Many of Alexandria’s former mayors are buried here including; E. R. Biossat, William Turner, Jr. and John Foisy. George Barrett was a councilman along with Napoleon Lawrence. Hippolite Labat served as a teacher, police juror, a Confederate tax collector and a United States Assistant Marshall. Jesse Atherton Bynum served as a U.S. Congressman from his native state of North Carolina before the Civil War and failing health brought him to Alexandria. His monument reads: “ardent in his attachments, sincere in his politics and devoted in love for his country”.

Antebellum Alexandria was never a healthy place to live. Life on the frontier was often cut short by violence. Seasonal flooding led to outbreaks of malaria, typhoid, cholera and yellow fever. The aura of tragedy surrounds many of the monuments in the cemetery. The beautiful obelisk monument of the Mead family records one of the saddest stories. Joshua and Lucy Mead are buried here together with six of their children. Five of these children died within three years. Three of the siblings died within an eight-day period in May of 1837. Their mother, Lucy, died the following year at the age of 40. John Brown and three of his children died in a three year span. Fanny Ryan, the young daughter of Michael Ryan, died in 1867 from yellow fever as a boarding student at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Natchitoches. John S. Fant lost his mother and oldest daughter on the same day in 1909. The grave of Miriam Ravencamp Hyams tells the sad tale of how the nine-year-old died in the collision of two Red River steamboats in 1844. Charles and Cornelia Kilpatrick buried four of their children in a period of six years. Robert Crain, one of the survivors of the notorious Sandbar Duel of 1828, is buried here along with R. L. Turner whose tombstone simply reads “Assassinated October 1st, 1882”. Welch Baillio, the town constable shot by Joseph Timberlake in 1897, lies here.

Alexandria’s position as a community center drew in others from the surrounding area for professional services not to be had in the wilderness. Dr. John C. Rippey, “born in the State of Pennsylvania 3 Dec. 1776” died at “Rapides 12 Jan. 1822” at the age of 45. Other famous physicians who served our community are buried here as well, including Dr. John Casson, Dr. Julius Johnston, Dr. James Fish and Dr. Smith Gordon. These men were among the organizers of the first Rapides Parish Medical Society in 1880. In addition to the lawyers and doctors, scores of tradesmen provided for the material needs of the town. John Schwartzenburg came from Vienna and opened a hotel and mercantile in Pineville before his descendants opened the family department store in downtown Alexandria. Francois Barbier was a baker in Pineville. John David, who immigrated from Bordeaux around 1825, was a successful merchant.

The gravestones also tell the story of immigration and of those who came looking for liberty and new opportunities. The French and Spanish came as part of the great colonial adventure. Families like the Wells and Thornton clans came from older settlements along the eastern seaboard. They came looking for virgin soil in Spanish Louisiana and found some of the richest alluvial soil in the world. Belgian and German immigrants came before the Civil War along with the Irish and Scots. The Syrian, Lebanese and Italian immigrants came later, during the first days of the railroad and timber booms. Numerous markers include a place of birth along with a birth date, indicating either homesickness or a desire to mark the great distance many had traveled in life. Many of these markers bear the same place of origin such as Cefalu in Sicily. The D’Angelo, Citrano, Matassa, Giordano, Distefano, Glorioso, Camilliere, Cataldie, Sardegna, Feduccia families all originated from that one spot.