As we move into October, we approach the time for goblins, spooks and things that go bump in the night. For the Celts, this is of course the time when “the veil” is at its thinnest, allowing the crossing between the spirit and the mortal world. All this brought to me the pondering of the customs of death and how they have changed in art throughout the ages. So I thought I might give you a little background on the sarcophagus as a venue of burial. Most of us don’t rate such a grand burying box, but notables of history have often been placed in some pretty lavish tombs.

The Etruscans were well known in their day for extravagant and quite realistic sarcophagi. The Cerveteri (Italy) Sarcophagus, c. 520 BCE, is a large painted terracotta monument. An effigy of a couple reclining on a dining couch adorns the lid. There is no parallel to this sort of tomb in Ancient Greece. Unlike the Greeks, the Etruscans embraced a uniquely modern view of women. For example, it would have been unthinkable for a Greek woman to attend a symposium, the celebrated institution of wine, music, poetry and debate. Etruscan women, however, would have been welcomed at such an event. They retained their own names and could hold property. This couple is obviously enjoying a symposium-type banquet.

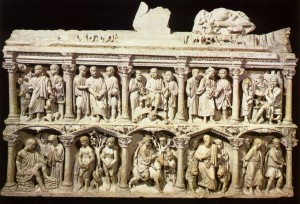

Romans gradually adopted the custom of burial, abandoning their earlier cremation practice, no doubt through the influence of Christianity. As burial became more popular, so did the demand for sarcophagi. And it seems that the more decorated, the better! Myths of the gods and goddesses were popular themes; their immortal faces replaced with the face of the deceased. Sarcophagi sculpting became a major industry in the late Roman Empire. We know that the craftsmen had pattern books from which to sculpt the decoration. These were often made before being sold to the family of a deceased loved one so space was left to fill in a familiar face. Western sarcophagi were usually decorated only on the front whereas their Eastern counterparts were decorated on all four sides. The lid was always reserved for an effigy of the deceased.

The early Christians adapted the Roman style, substituting Christian subject matter. A sarcophagus in the Church of Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome (c. 270), illustrates some of the universally appealing themes. A philosopher and an orant figure take center place. The story of Jonah appears to their right while Christ, the Good Shepherd and a scene of the baptism of Christ adorn the left.

One of my favorite tombs is that of Constantia, daughter of the Emperor Constantine. It is believed that her tomb was originally placed directly below the dome in the central-plan church of Santa Costanza, just outside Rome. Constantia’s sarcophagus can now be seen in the Vatican Museums. It is made of porphyry, a purple hued rock that was a favorite for imperial sculpture.

Throughout history nobility and other important people have been laid to rest in highly decorated tombs. The sculpture spoke volumes of their lives, their deeds, and often their misdeeds. What would the sculptor create for yours?